The peacock is one of the natural world’s most elaborate and showy males, mustering its physical resources to wow potential mates with its enormous and gaudy, fan-like tail plumage.

Now scientists in China say they have uncovered the exact mechanisms used by one species to produce the iridescent green, blue, yellow, and brown tiny feather tips that comprise the bird’s distinctive ornament.

“The male peacock tail contains spectacular beauty because of the brilliant, iridescent, diversified, colorful eye patterns,” said Jian Zi, a physicist at Fudan University in Shanghai, China, and lead author of the study published online earlier this week in the science journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Male peacocks shed and re-grow tail feathers each year. The plumage is prized throughout the world as an exotic decoration.

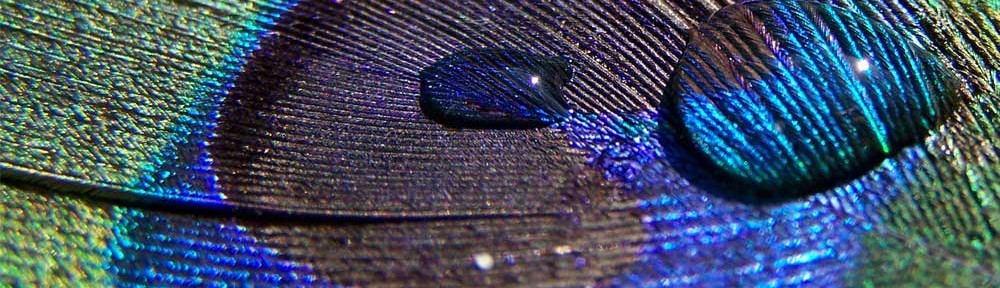

Researchers found that the feathers’ bright colors are produced not by pigments, but rather by tiny, intricate two-dimensional crystal-like structures. Slight alterations in the spacing of these microscopic structures cause different wavelengths of light to be filtered and reflected, creating the feathers’ many different iridescent hues.

Researchers found that the feathers’ bright colors are produced not by pigments, but rather by tiny, intricate two-dimensional crystal-like structures. Slight alterations in the spacing of these microscopic structures cause different wavelengths of light to be filtered and reflected, creating the feathers’ many different iridescent hues.

Simple and Ingenious

Sir Isaac Newton, the 17th- and 18th-century British mathematician and physicist, was among the first to suggest that tiny, layered structures were responsible for producing color in peacock feathers, and other iridescent insects and birds.

But until now, the exact physical mechanism by which different colors are produced has not been known, said Zi. “Our work has [now] revealed … ingenious and simple mechanisms of color production in peacock feathers,” he said.

Most of the color we see in nature is due to pigmentation, substances that selectively absorb light at some wavelengths and reflect it in others. Plant chlorophyll, for example, absorbs and reflects all wavelengths of light except green. Other examples include pigments that produce the color in human hair and skin.

But some animals have hit on a completely different evolutionary strategy, using microscopic, translucent structures to selectively filter and reflect light. Examples of such structure-generated colors can be seen in shimmering metallic butterfly and moth scales, beetle wing cases, and the feathers of hummingbirds, peacocks and birds of paradise. Similar reflective structures made from silica are also responsible for the shimmering color found in opals.

Stunning Souvenir

One of the oldest displays of such a structural color scheme, known as a multi-layer reflector, was found in a 50-million-year old beetle fossil unearthed in Germany. The fossil still displayed the bright blue shade it wore in life.

Zi’s motivation to study peacock coloration came after a trip to the marketplace in southern China’s Yunnan province, where he bought a bundle of peacock feathers from Banna (a town renowned for its wild peacocks) as a souvenir. “When I watched the eye pattern against the sunshine, I was amazed by the stunning beauty of the feathers,” said Zi.

To uncover the basis of that color, Zi and colleagues used very powerful electron microscopes to examine the barbules of the green peacock, Pavo rnuticus. The barbules are the tiny feather tip structures that come off of barbs on either side of the central stem of peacock feathers.

When viewed under a microscope, they revealed a repetitive two-dimensional structure of small crystals—each with a width hundreds of times thinner than a human hair. Optical measurements and calculations showed that variation in the spaces between repeats of the crystals causes the structures to reflect light in slightly different ways and leads to variation in color.

Dressed to Impress

“Structural colors are often found in animals that wear the color as a function to be conspicuous,” commented Andrew Parker, an evolutionary biologist and coloration expert at the University of Oxford in England. Such color mechanisms are often much brighter and visible over longer distances than pigments.

Charles Darwin was one of the first scientists to argue that female peacocks prefer the males with the boldest and most attractive ornaments, and subsequent work has shown that brightly decorated males enjoy greater mating success. Studies have also shown that the quality of ornamentation in peacocks is an accurate reflection of the state of the immune system, so females are picking those males genetically predisposed for tip-top health.

Discovering so-called photonic crystals in peacock feathers could allow scientists to adapt the structures for industrial and commercial applications, said Parker. These crystals could be used to channel light in telecommunications equipment, or to create new tiny computer chips. We can take advantage of “millions of years of evolutionary trial and error,” for new technologies, he said.